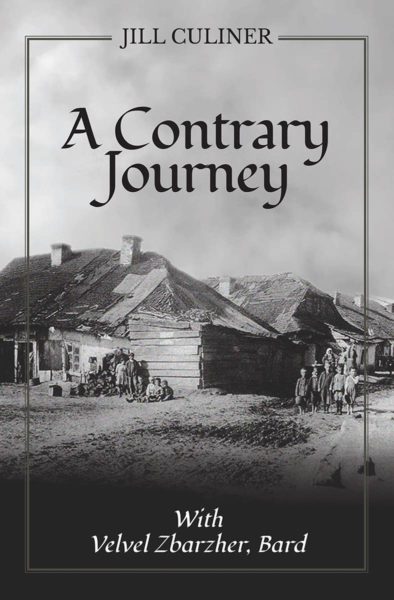

We are excited to share with you a new book by Jill Culiner. Entitled A Contrary Journey. It tells the story of the Jewish enlightenment. Jill follows Velvel Zbarzher, a bard in the 19th-century Old Country. There the poet fought for universal education and freedom of expression as he traveled, sang, and argued his way from Eastern Europe to Turkey. Here Jill shares with us the highlights and her personal journey of discovery, both in a short video and with her story below.

More information, including purchase options and the author’s bio below.

Start with this short video

The Jewish Enlightenment: A Contrary Journey by Jill Culiner

The beginning of this contrary journey . . .

A frustrated child, I longed for worlds I would never see. I wanted the treacherous deep woods found in fairy tales, castles where princesses lived, or the corrupt London described by Dickens. Later, Balzac, Fielding, Smollett, and Maupassant stirred my imagination. Then, thanks to Mendele Mocher Sforim and Sholem Aleichem, I encountered the Old Country’s cranky characters and twisted streets.

That unknown Old Country: I even had people around me who could give me first-hand information, my grandparents.

“Tell me about what life was like back then,” I begged them. “Tell me what things looked like.”

They only shrugged: “That won’t interest you.”

Their refusal fired my curiosity. I wanted to see the shtetlech, the Jewish sections of towns and villages. I wanted to stand in dusty main squares or chaotic markets, to frequent local inns; I craved unknown sounds and odours. But time passed.

Thirty years later . . .

Thirty years later, communism ended. I could travel in Eastern Europe, live there, see what was left of the past, and even find the former family inn. I could discover what life had really been like; for, until twenty years ago, we were fed a romanticized version of the shtetl. Heritage tour patter still keeps up the illusion, yet, despite myth, those shtetlech weren’t ideal cosy communities where solidarity, kindness, love, and pious warmth reigned. They were like villages everywhere.

Life in each shtetl was woven into that of the next by marriages, market days, trade fairs, and by those who traveled between them: musicians, predicators, the badkhonim or wedding jesters, merchants, weavers, shoemakers, water carriers, drovers, roofers, sawyers, farmers, wagon drivers, wainwrights, blacksmiths, peddlers, and hawkers. The shtetlech were small enough for people to be known by both their name and an often-brutal nickname: Clubfoot Yankel, No Underwear Schwarz, Stinking Avru, or Old Maid Chantzah.

Life in the shtetlech . . .

Some residents were friendly, some were kindly, some were awful, some were horribly poor, others were wealthy with high status. Those at the bottom of the Jewish social barrel, water carriers, or unmarried girls from poor families, were constantly reminded of their inferior status by vicious comments, mockery, and cruelties.

Close to this low social grade were the so-called illiterates, the workers and craftsmen who, as adolescents, had been apprenticed or sent off to labor in factories. They didn’t attend Talmudic schools; they were less steeped in religious knowledge; they mixed with Christians in the working world. Discriminated against in religious ritual, they were only allowed to participate in additional readings after the Torah service.

Learned men stayed home studying, or they gathered in study halls and back-street prayer houses. Women ran family businesses, inns, or small shops selling cloth, aprons, scarves, ribbons, tar, and resin. Only a tiny minority of girls attended a few years of cheder, the traditional elementary school. Most remained home, acquiring business skills, helping with household duties, raising younger brothers and sisters, learning the Tekhines, the Yiddish supplications, prayers, and religious obligations.

The Jewish enlightenment . . .

Jewish life was ruled by Hasidic rebbes or the traditional Mitnagdim, and religious law dictated every aspect of daily life. Secular books were forbidden; independent thinkers were threatened with moral rebuke, magical retribution, and expulsion. Yet, in the big wide world, the nineteenth century was a time of great change, of cultural wealth, questioning, experimentation, and discovery.

It was a time in which old social orders were being overthrown. In the Jewish world, the Enlightenment, the Haskalah, begun in Germany a century earlier, was now challenging the religious stranglehold in Galicia, Romania, and the Russian Pale.

The maskilim, proponents of the Enlightenment, were determined to create a modern Jew, to open the door to secular education, to found schools where children were free to learn science, geography, languages, history, and philosophy. They were demanding freedom of thought and movement, the right to read and write modern literature, to create plays and act in them, to question belief, or refuse it altogether.

But life was not easy for such rebels. Rejected by their families, banished from their villages, they gathered in cities such as Brody, Lvov, Vienna, Warsaw, and Odessa, and knew the exile’s misery. But they did have one thing in common: they were starting anew, abandoning frustration.

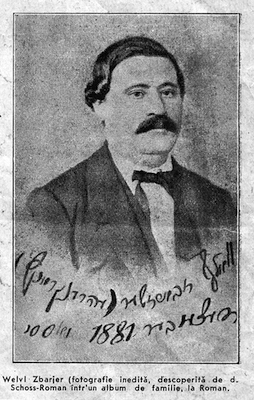

Velvel Zbarzher

Velvel Zbarzher (Benjamin Wolf Ehrenkranz) was born in 1826 in the shtetl of Zbarazh, now Ukraine, then Austrian Galicia. A maskil poet, he was considered heretical by the local Jewish community and forced into exile. He spent the rest of his life singing his Hebrew and Yiddish poems to a loyal audience of poor workers and craftsmen throughout Galicia, Romania, in Vienna, and Odessa. In 1880, he went to Constantinople and married Malkele the Beautiful, the woman he had loved for many long years. Three years later, he died.

I first discovered Velvel in Sol Liptzin’s History of Yiddish Literature, and it was this one sentence that particularly snagged my interest:

Zbarzher…might well have attained the pinnacle of fame…if he had not squandered his talent in disreputable Rumanian inns and Turkish coffeehouses.

I longed to squander my talent in disreputable nineteenth-century inns, to find that vanished world. I craved villages where there was a silence we don’t know today; I wanted hawkers, blacksmiths, and pot menders; I needed to hear the sort of music that has now vanished. Above all, I dreamed of meeting Velvel, finding the houses where he’d lived, the towns he’d passed through, and of lurking in those fusty inns where he’d sung.

Do come and join me. We’ll take to the road together, and I’ll show you what can be found.

(Available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Waterstones, Blackwells, Better World Books, Alibris, Better World Books, Abe Books, and Claret Press)

How about you? Aren’t you curious? Don’t you want to travel back to the mid-1800s in Eastern Europe?

Photo Credits

Author Jill Culiner supplied all photos on this page. Used with permission.

As I’m from the UK I’ve travelled quite a lot through Europe and the buildings which housed Jewish communities are always a fascinating part of trips. I know very little about the history though, so this seems like an excellent place to educate myself a bit!

Hello, Fiona. Yes, this is a forgotten part of history, and Velvel Zbarzher is a long-forgotten poet. This story brings that time back to life again.

wow sounds like an interesting life story mixed with a bit of history! Can’t wait to give it a read!

Yes, Soheila, it’s many things: a biography, a travelogue, a history. There’s humour, too. Hope you enjoy it.

Although I am Christian, I’m fascinated by Judaica, especially since being blessed to travel to Israel.

Israel is certainly a fascinating country, and the study of any religion is always interesting. Jewish life changed radically in Eastern Europe in the 19th century, and I loved researching this period.

Thank you for the review on this. I am eager to read it!

Hope you enjoy it, Rachel. Thanks.

This has added more knowledge to me about Jewish faith. I really enjoy the reading. Thanks for sharing

I don’t know a whole lot about the Jewish faith, but this sounds incredibly interesting.

Thanks, Krysten. This was an interesting period in Jewish history, but there is also some information about the Christian peasant world in Eastern Europe.

I don’t read that many books anymore but this writer seems to have a way with words

Thank you, Renata. Saying I have a way with words is the sort of comment that would please any writer.

looks like a very interesting read to me. I don’t know much about Jewish history apart from school lessons, it seems like a nice option to educate myself more

There is also general history in the book, but I hope I’ve presented history in a lively, colourful way. I want readers to be able to smell, hear, and feel the villages. It was an interesting period.

I actually love how you had described till the end of the story. I would love to read it. Great review.

Thank you. Do read it! It’s a journey into a world that’s been forgotten.

What a great review! I don’t know much about this history so this was so interesting to read!

I honestly didn’t know much about the Jewish faith and religion until recently. One of the new scouts in my den is Jewish and I have learned a lot from them.

In a globally connected world, I am glad that Jewish community is bringing attention back to it’s salient features

I certainly agree.